Titanium CNC Machining: Mastering Precision for Aerospace Flanges

In high-performance engineering, the strength-to-weight ratio isn’t just a metric; it is the defining constraint of the project. Whether we are discussing a linkage in a Formula 1 suspension or a fuel system component in a commercial jet, the material choice often lands on Titanium.

However, selecting Titanium is the easy part. Machining it to tight geometric tolerances without compromising the material integrity is where the real engineering happens.

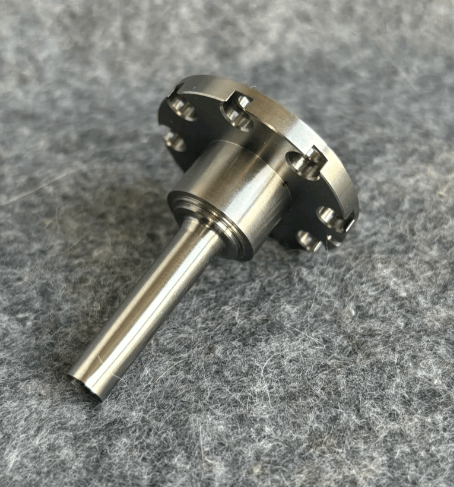

At Rapid Model, we see thousands of designs pass through our shop floor in Shenzhen. The component shown in the image above—a custom Titanium flange shaft—is a textbook example of why this material is both loved by designers and respected (sometimes feared) by machinists.

This post dives into the technical realities of Titanium CNC machining, analyzing the specific challenges of interrupted cuts, work hardening, and maintaining concentricity in turned parts.

Visual Analysis: More Than Just a “Grey Part”

Looking closely at the image provided, we are likely looking at Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5). This is the workhorse alloy of the aerospace industry. The visual cue is that distinct, darker premium grey luster that differs significantly from the brighter, silver tone of Stainless Steel (304 or 316) or the matte white of Aluminum.

Key Features of the Component

- The Shaft: A turned cylindrical section requiring high surface uniformity (likely Ra 0.8 or better).

- The Flange: A perpendicular face integrated into the shaft.

- Interrupted Cuts: The bolt pattern (holes) around the flange.

- Chamfers: Precision edge-breaking on the holes to prevent stress risers.

While this part looks simple to the untrained eye, a mechanical engineer knows that the combination of a slender shaft and a drilled flange introduces significant machining variables.

The Technical Challenges of Machining Titanium

Why is this part difficult? It comes down to the thermal and physical properties of the material. Unlike steel, Titanium has low thermal conductivity. It doesn’t dissipate heat into the chip; it concentrates heat at the cutting edge.

1. Combating Work Hardening in Drilling

The flange in the image features a series of counterbored or chamfered holes. Drilling Titanium is risky. If the drill dwells (spins without cutting) for even a fraction of a second, the material work-hardens instantly. The surface becomes harder than the substrate, leading to immediate tool failure.

To achieve the clean chamfers seen in the photo, we utilize:

- High-pressure coolant: To blast chips away and manage heat.

- Sharp Carbide Tooling: Coated specifically for heat resistance (often TiAlN).

- Confident Peck Cycles: We don’t “baby” the cut. We maintain a constant feed rate to ensure the tool is always shearing material, not rubbing against it.

2. Interrupted Cuts and Tool Shock

The holes on the flange represent “interrupted cuts.” When a turning tool or end mill moves across these voids, it experiences a rapid load/unload cycle. In Titanium, which is somewhat springy (low modulus of elasticity), this can cause vibration or “chatter.”

Chatter is the enemy of surface finish. To produce the smooth finish seen on this flange, our CNC machining services rely on high-rigidity machine setups. We minimize tool overhang and use vibration-dampening tool holders to ensure the finish remains consistent despite the interrupted cutting path.

3. GD&T: Concentricity and Perpendicularity

The most critical feature of this part is likely the relationship between the shaft axis and the flange face.

- Concentricity: The shaft must be perfectly round.

- Perpendicularity: The flange face must be exactly 90 degrees to the shaft.

If these are off by even a few microns, the assembly alignment will fail. At Rapid Model, we typically machine parts like this on a Mill-Turn center. This allows us to turn the shaft and mill the flange holes in a single setup. By not removing the part from the chuck between operations, we eliminate re-fixturing errors, guaranteeing superior Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T) adherence.

Material Selection: Titanium vs. Stainless Steel

I often ask my clients: Do you prefer machining Titanium or Stainless Steel?

While Stainless Steel (like 316L) is gummy and prone to building up on the tool edge (BUE), Titanium is abrasive and hot.

- For Prototyping: If you are in the validation phase, our rapid prototyping division often recommends starting with Aluminum for fit-checks to save cost, before moving to Titanium for functional testing.

- For Production: Titanium is non-negotiable for aerospace due to the strength-to-weight ratio.

Surface Finishing: The Final Touch

The part in the image has a machined finish, but Titanium responds beautifully to post-processing.

- Bead Blasting: Creates a uniform matte texture.

- Anodizing: Titanium can be anodized without dye (using voltage to change the oxide layer thickness) to produce colors for identification or aesthetics.

Proper surface finishing is not just cosmetic; it can also improve fatigue life by removing micro-machining marks that could act as crack initiation sites.

The Rapid Model Advantage

Machining Titanium requires a mindset shift. You cannot simply run standard steel speeds and feeds. It requires a “low speed, high feed” strategy to manage thermal loads.

At Rapid Model, located in the manufacturing hub of Shenzhen, we combine ISO 9001 quality standards with advanced 5-axis and Mill-Turn capabilities. Whether you need a single complex prototype or a run of 5,000 aerospace fasteners, we understand the physics of the material.

We deliver:

- Material Certification: Genuine Ti-6Al-4V with full traceability.

- Precision: Tolerances down to +/- 0.005mm.

- Speed: fast turnaround times for global clients in the USA and Europe.

Conclusion

The Titanium flange shown here is a perfect representation of precision engineering. It balances geometric complexity with difficult-to-machine material properties. Achieving that level of precision requires more than just a CNC machine; it requires experienced engineers who understand how to control heat, vibration, and tool wear.

If you have a complex design involving Titanium, Inconel, or other superalloys, don’t leave the manufacturing to chance.